Terror Down Under: The Evolution of Cultural Anxiety, Isolation, Landscape, and Dystopia in Australia Literature

Australian Literature as a Reflection of Sociopolitical Change

When asked to describe the Australian colonial experience, images of the rugged, white, Australian bushman come to mind, first introduced in primary school classrooms, the story of the courageous and tough white settlers is one of national pride. Australian history and national identity have long been carefully curated; a country of fierceness, of toughness, and of survival. From colonial writing to now, the image of the Australian bushman, fearless and domineering, is a recognisable symbol of the country. Australian history is undoubtedly marked by change, by colonisation, and by widespread cultural amnesia. However, the carefully constructed Australian identity is fractured by many novels and texts that instead tell a different narrative – one of fear, of terror, and of isolation.

Throughout Australian literary history instead these themes are consistently present, from pre-colonisation to contemporary times similar tales of terror are told. This alternate experience of fear and isolation beginning in colonial times offers an interesting perspective into the evolution of Australian identity. These themes of fictional monstrosity and landscape are typical of the contemporary genre of dystopia, although many of the texts could not labelled as explicitly dystopian, it is the development of these themes of dystopia that are ever present and all-telling. As well as this, the consistency of these themes throughout literature spanning almost half a millennium is a testament to the Dystopian genre’s ability to reflect society and thus offer insight into the evolution of the nation. Therefore, regardless of these texts being written prior to the ‘invention’ of dystopia itself they offer important insights into the development of the themes and thus genre. Literature is a crucial tool of both reflection and prediction and the difficult topic of Australia’s past is contained within the pages. This leads to the questioning of what experiences have been ignored throughout Australian history and the key question of:

How is the evolution of Australian national identity reflected through the development of dystopian themes of environment, fear, and monstrosity in literature from 1788 to present?

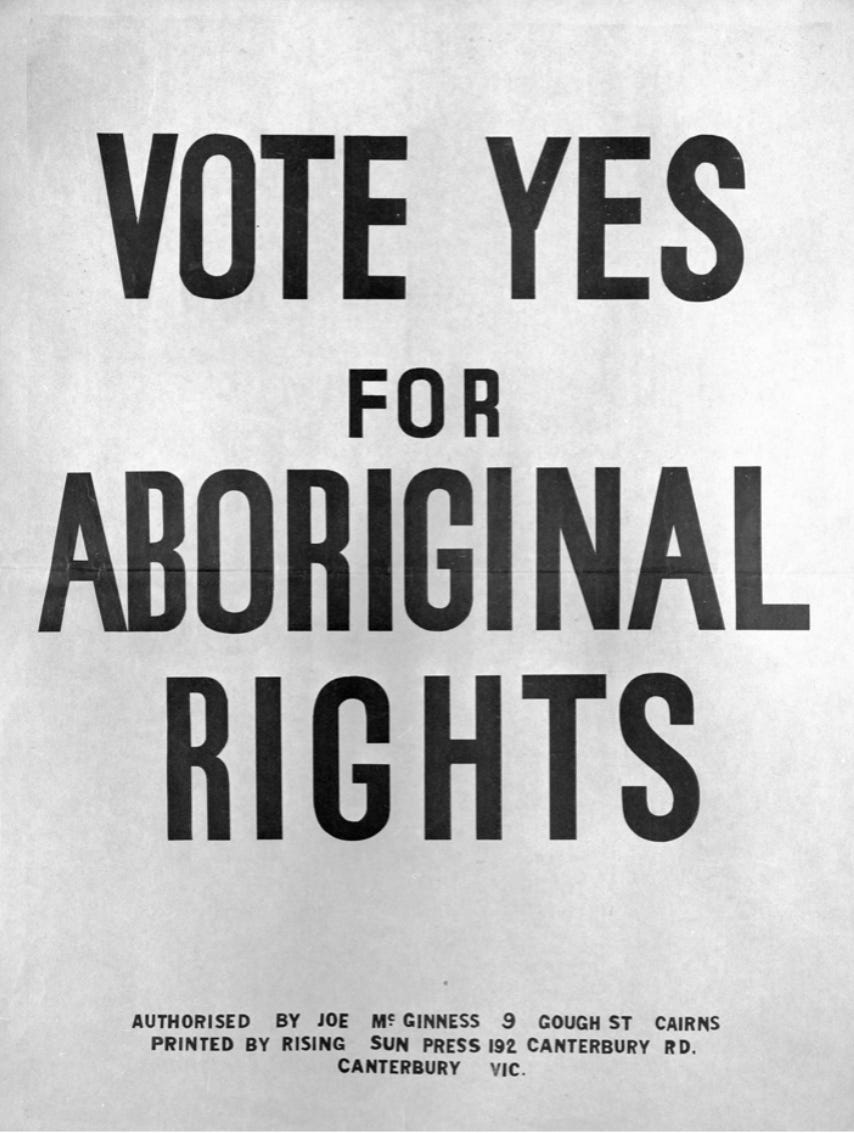

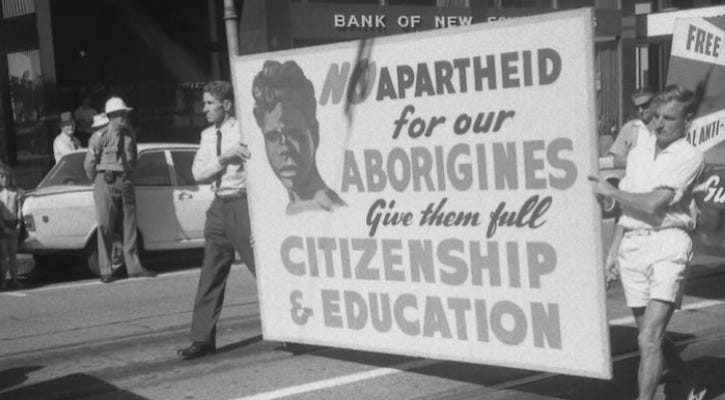

Although the term ‘dystopia’ itself was not coined until 1868, the themes central to the genre are of the utmost importance in understanding Australian literary history. Understanding the formation of Australian identity within literary representations allows conclusions to be drawn regarding the historical experiences that continue to affect society. Fiction is often over-looked as a powerful tool of historical inquiry, stories of adventure and of struggle across Australian history are timeless depictions of humanity and of society. The themes of dystopia simultaneously exist within pre-colonial texts and contemporary retellings, this continuity of the genre emphasises its importance. Nevertheless, to understand this development, key time periods will be compared. It is important to recognise these periods have been selected to assist in understanding the development of themes and the key historical events that inform them. Pre-colonisation ‘Terre Incognite Australis’ was a figment of imagination, from here, the early colonial period spans from 1788 to 1901, followed by the 1901 unification beginning the period of post unification (1901-1967). Moving into a time of post-colonialism and a changing political atmosphere, the next focus period begins with the 1967 Referendum on Aboriginal rights. Finally, the contemporary resurgence of this genre will allow a complete history of change and similarity to be mapped.

Pre-Colonisation:

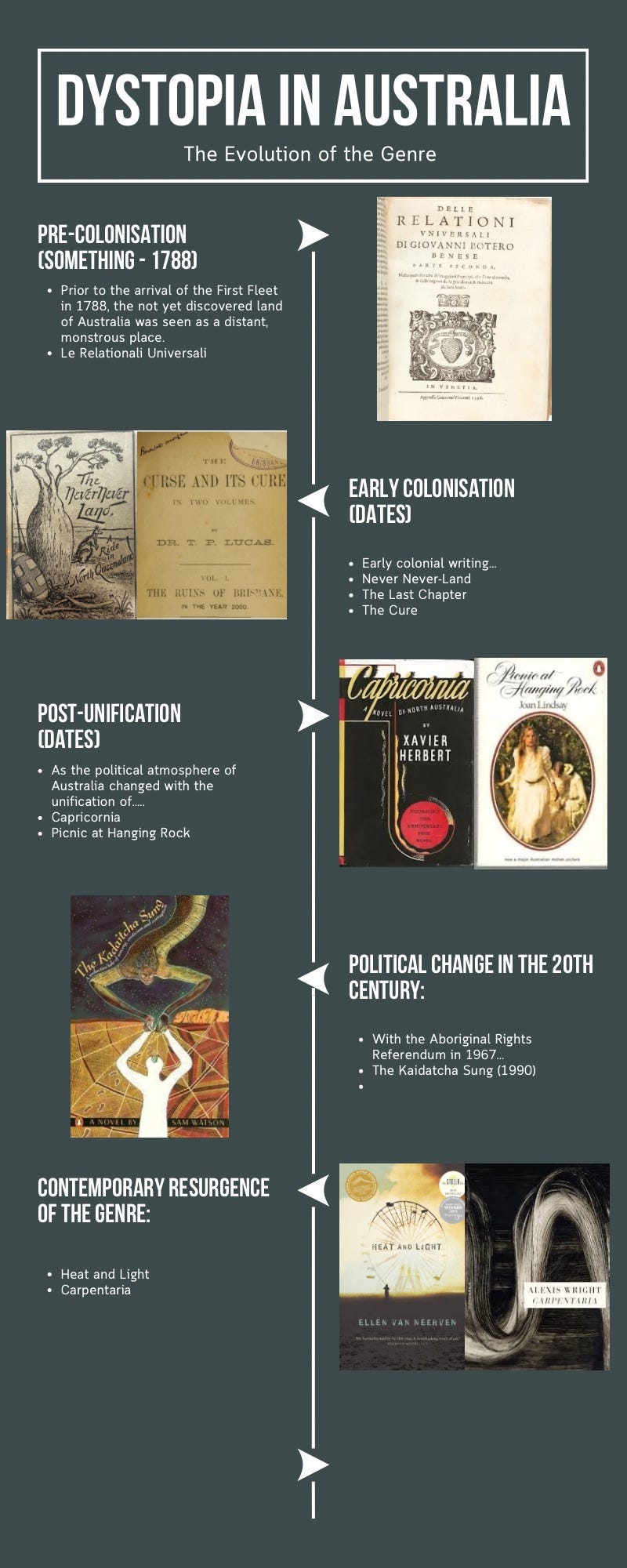

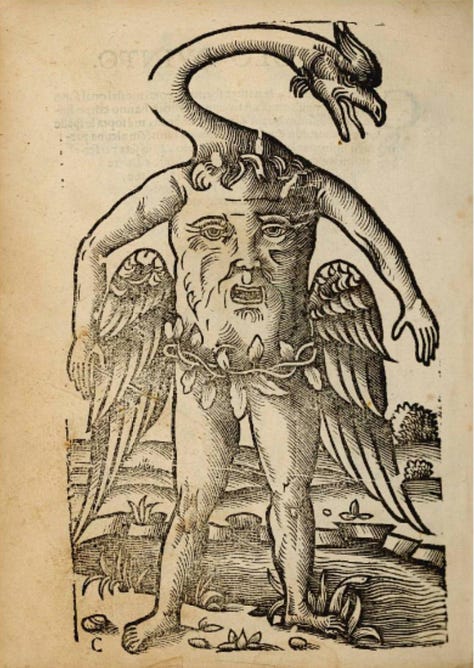

Prior to colonisation, the not yet discovered land of Australia was already the focus of many fictional and geographical accounts of monstrosity and terror. Giovanni Botero (1540 – 1617) published Le Relationi Universali in Venice, Italy in 1591. Republished in 1617 by Alessandro de Vecchi complete with wood carvings and large maps, the text was considered the best global geography available at the time.[1] Read through a contemporary lens, the text seems like fantasy literature of unknown worlds and figures of the imagination, however, it was an extensive and legitimate collection of maps and geography. The book contained four large, folded maps and thirty-two woodcuts, towards the bottom of the map of Asia a mass titled “Terre Incognite Australis” is detailed. Following this map, the beginning of Australia’s representation as a land of terror is detailed. Within the thirty-two woodcuts, two offer illustrations of the creatures of Terra Incognita. With human heads and webbed feet, muscular torsos and horse bodies these creatures were imagined to be inhabiting the distant land. This begs the question of the origination of Australia’s representation as a land of fear, prior to discovery was it seen only as a place of expansion and opportunity as often told or a lost land of terror filled with petrifying creatures?

Early Colonisation (1788 – 1901):

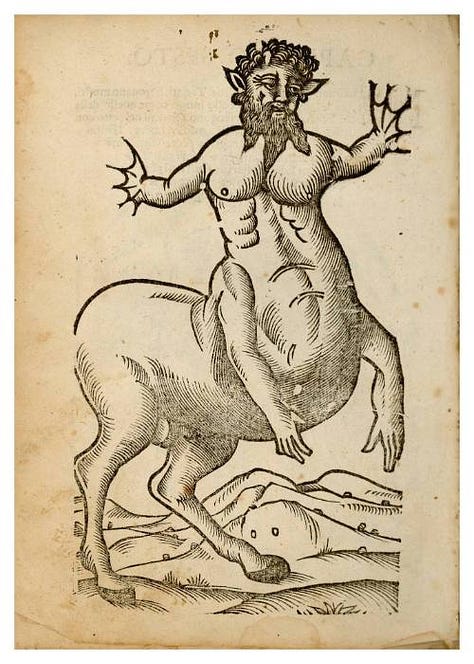

Almost 200 years later upon the discovery and subsequent colonisation of the ‘distant land’ of Terra Incognite, similar themes of dystopia continue to be found within early Australian writing. Although less fantastical, upon colonisation many settler accounts represent the landscape and experience of Australia itself as monstrous. Depicted consistently as a place of extreme isolation, the settler experience of loneliness, of fear and of ultimately anxiety is reflected within many examples of colonial fiction.[2] A main theme of landscape and its significance to the settler experience becomes increasingly apparent. Tales of exploration and opportunity are contrasted with fictional stories of death, of complete loneliness and of the violent Australian landscape within Never Never Land (1884), The Last Chapter (1889), and The Curse and it’s Cure (1894).

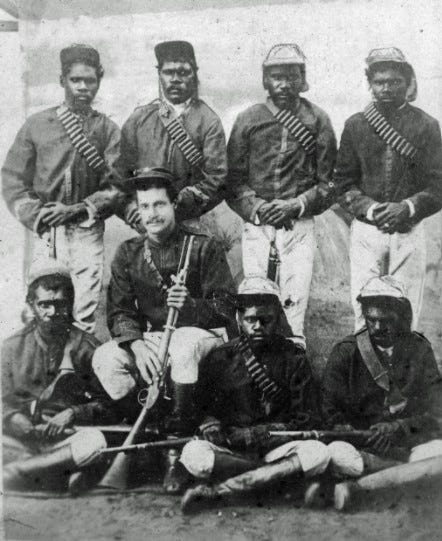

Never Never Land: A Ride in North Queensland is a tale of the inherently violent atmosphere of Northern Queensland by Archibald William Stirling. A story of his travels throughout Northern Queensland and thus an important account of settler experience, the very phrase itself ‘the never never’ used to describe the area North-West of Rockhampton alludes to the settler anxieties of isolation and specifically the threat of Indigenous uprising. Stirling details the isolation, the fear, and the way the landscape of this ‘never never land’ inspires violence within his 1884 account. With literature as the mirror of society, it is important to consider the historical context of this text. The area deemed the ‘never never’ was an area of great instability, violence and genocide at the time of Stirling’s travels.[3] The Kalkadoon people of Mount Isa could be considered one of the best examples of Aboriginal resistance to colonisation as one of the last tribes to encounter Europeans.[4] Although Stirling does not detail personal experience with the Kalkadoons, it can be concluded that these violent events are reflected within his writings due to the close proximity of the two. In September of 1884, after significant ‘native uprising’ from the Kalkadoon people where five native police were killed, the Sub-inspector of the Queensland Police Urquhart enlisted the Native Mounted Police and pastoralists to seek out and remove the threat of the Kalkadoon. Signifying the historical significance, the sight of this violence is known today as Battle Mountain, over 600 Kalkadoon soldiers were killed, and the fleeing men, women and children were massacred.[5] Therefore, the themes of fear, of violence, and of an inherently dangerous landscape contained within settler writings reflect the settler experience of anxiety and isolation similarly illustrated by William Stirling in The Last Chapter (1889).

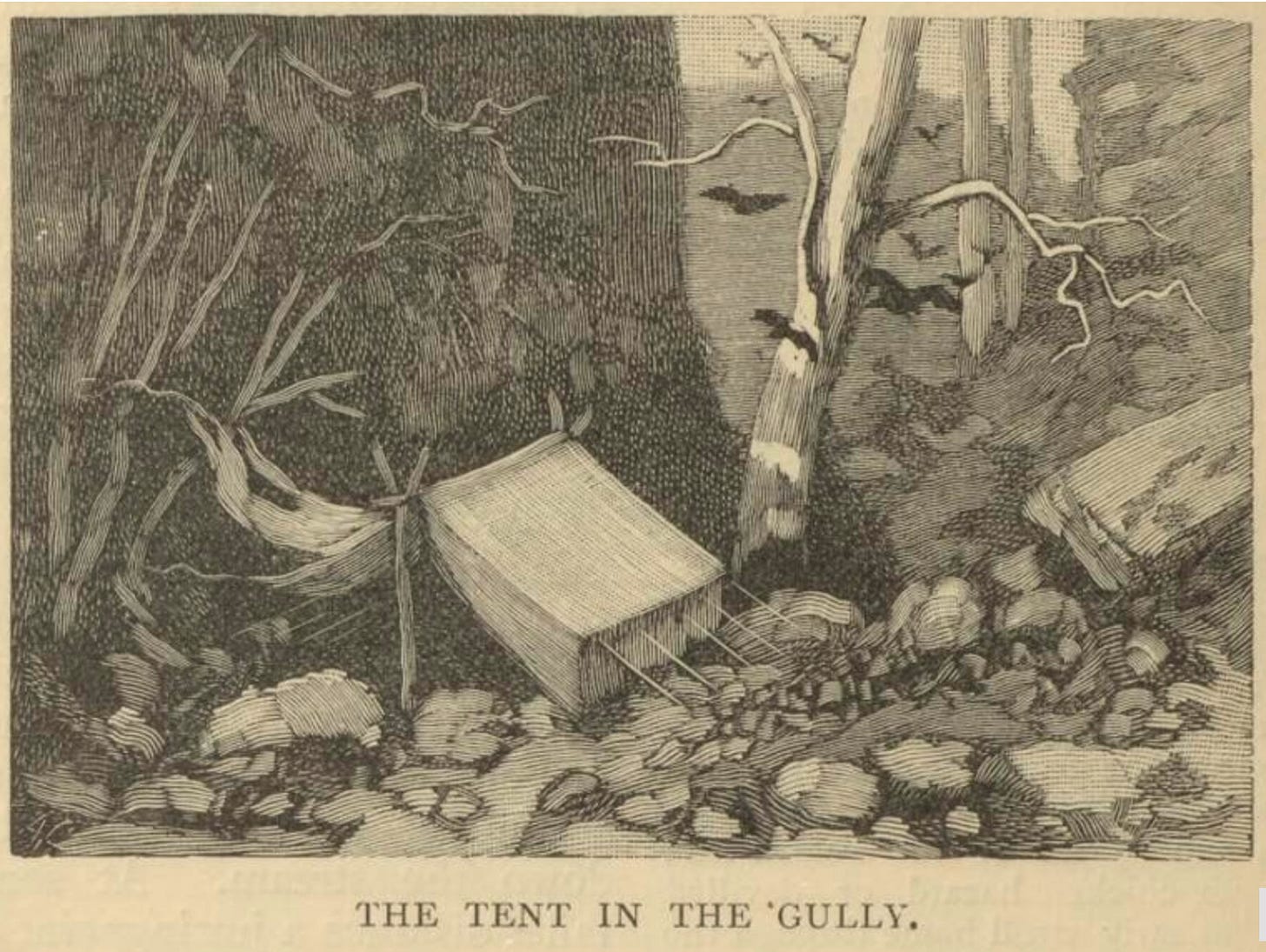

William Hodgkinson’s The Last Chapter captures the violence and conflict of the colonial period in a fictional story of a settler hunting down the supposed killers of a prospector in Northern Queensland. Similar to Stirling, landscape plays a pivotal role within this text with the story centred around the brutality the land brings about. This is emphasised by the conclusion of the narrative, when the team find the murderers, the main character is overcome with “the lust of the Berseker” and massacres an Aboriginal camp. His ‘civilised’ nature seen throughout the narrative is juxtaposed with the complete violence and disproportionate need to kill the bush induces. On page 776 of the novel, the tent where the prospectors' dismembered body is found is illustrated overgrown with nature.

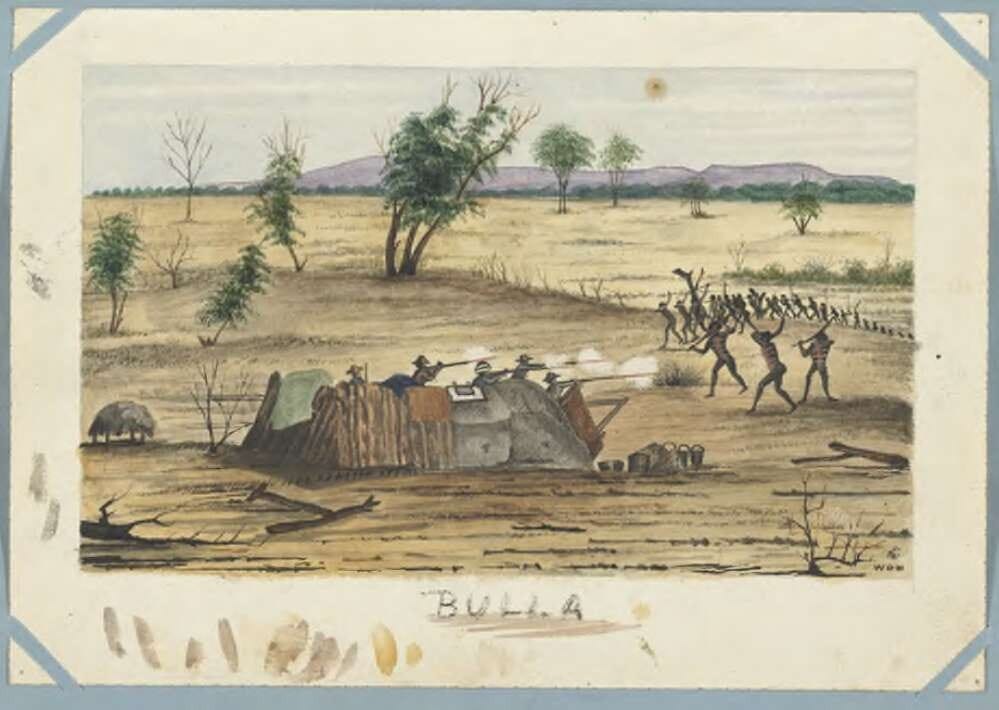

Within the illustration the tent is almost swallowed by the landscape surrounding it, a dark background adding to the fearful atmosphere. Similar to William Stirling, William Hodgkinson’s novel reflects his personal settler experience of isolation and of fear of Aboriginal uprising and the landscape itself. Hodgkinson was an eyewitness of the 1861 battle between the Bulla (Bulloo) people and European settlers. His own experience of battle and of ‘Aboriginal uprising’ is thus reflected within his fictional work. One of the most significant and memorialised unsuccessful expeditions of the time was that of Burke and Wills. Burke and Wills left from Melbourne to attempt to explore the Gulf of Carpentaria, however, never ended up returning. Multiple expeditions were held to find Burke and Wills concluding with the discovery of their malnourished bodies. Hodgkinson was a part of the 1861 Victorian Relief Expedition from Rockhampton where upon contact with a battle was fought ending in the deaths of twelve Aboriginal people seen within his painting titled “Bulla.” Within the painting, the background contains massive ‘uncivilised’ bushland where the European stockade and Aboriginal ‘attackers’ are isolated. This purposeful representation of the bravery of the Victorian Relief Expedition is emphasised by the picture being given as a present to Hodgkinson’s romantic interest as evidence of his valiant travels.[6] Therefore, the anxiety and the fear communicated within Hodgkinson’s literary efforts is a mirror to the societal experience of terror and isolation of the time.

The reflection of distress and anxiety seen within the consistent theme of landscape and its inherently violent nature is continued within The Curse and its Cure (1894) by Thomas Pennington Lucas. The text differs from both Hodgkinson and Stirling’s experience of far north and central Queensland as the first ever published with Brisbane as its setting. The Curse and its Cure is more distinctly dystopian or even utopian than its predecessors; a story of the year 2000 and a trip along to ruins of Brisbane city the text hypothesises the possibility of an Aboriginal uprising causing the end of civilisation as known. Sailing along the Brisbane River, the narrator reflects on the undeniable force of nature turning the city to ruins. Although an implicitly racist text, where the end of ‘civilisation’ is caused by Aboriginal people gaining power, Lucas’ description of the landscaper also reflects a fear of what is around him. It is declared that “bush and forest hold extensive reign,” and that “nature rules in primitive sway.”[7] With all three of these men being European settlers it is important to recognise the stark contrast between their native environments in England and the land around them in Brisbane, Central Queensland and Northern Queensland. Although Lucas does not detail the landscape creating and inspiring unnatural violence as Stirling and Williams do, Lucas corroborates their fear and anxiety of the world around them.

Post-Unification (1901 – 1967)

Post-unification of Australia, the nation underwent a struggle to determine a strong national identity amid changing race relations, gender equality, and two World Wars. Landscape continued to be at the forefront of anxieties, however, as Australia moved away from being a nation of ‘settlers’ the themes of terror and monstrosity continued yet evolved into reflections of equality and change in Capricornia (1938) and Picnic at Hanging Rock (1967).

Capricornia by Xavier Herbert is a story of love, pain and humanity set in the Northern Territory, a distinctly Australian novel, this text differs greatly from the writings of the early colonial period due to its distinct commentary on Australian multiculturalism and cross-race relationships. A story of three generations, Capricornia is a massive epic that reflects the changing race relations of 20th Century Australia. Xavier Herbert’s novel was purposely published on the 26th of January 1938, when the first ‘day of mourning’ protests were organised.[8] The novel’s cynicism and satirical approach is impacted by Herbert’s experience as a child in World War I and his approach to race relations with both a Chinese-Australian and Aboriginal-European relationship at the forefront of the novel a testament to his own experience with a Jewish wife amid rising anti-semitism.[9] These relationships and its stark honesty about the punishment and abuse of Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory reflect a time of immense change in Australia society. Posthumously, Xavier’s first hand writings regarding the abuse on Northern Territory reserves became evidence for the Human Rights Commission into the Stolen Generation in 1997, almost 60 years after his book was published.[10] The novel’s setting of Capricornia is a loosely vaulted fictional version of Darwin in the Northern Territory. Herbert’s novel was a direct commentary on the ‘societal issue’ of ‘half-caste’ children or “yeller fellers” in the book. Nevertheless, the landscape and environment within the book is central to its narrative. Landscape is again represented as monstrous, isolated and a place of terror, however, it directly juxtaposes the prior novels instead utilising this description of landscape as a commentary on the devastating impacts of colonisation on the land. A similar tale of political and social change, Picnic on Hanging Rock tells a similar story against colonialism and repression through central themes of landscape.

Joan Lyndsey’s Picnic at Hanging Rock was published the same year as the 1967 Referendum on Aboriginal Rights, this text is a reflection of the evolution of Australian society and identity throughout the 20th century. Often described as a feminist text, Lyndsey’s mystery offers a reflection of nature, of repression and colonialism and of the unknown. A story of intense humanity, the purposeful ambiguity of the novel creates an atmosphere of mystery. Although this text is again not Dystopian in the context of genre, its significance as one of Australia’s ‘classic’ novels is undoubted and its utilisation of untamed landscape and isolation mirror each of the previous focus texts. The rock itself in the novel becomes almost personified – a massive presence to be reckoned with. This links to the significance of place in both Australian literary history and within First Nations culture. The rock’s existence as initially merely a picnic ground mimics Australian society’s attempt to whitewash history, within the text the girls are even forbidden to explore the nature and rock around them.The literal existence of the rock in Victoria as a place of traditional significance is an important factor in Lyndsey’s commentary on the connection between nature, colonialism and vengeance within the text. Similar to Xavier Herbert’s Capricornia, Lyndsey offers the perspective that the sanitation and amnesia regarding Australia’s genocidal history and repression leads to the death and destruction throughout the novel. The complete ambiguity of the conclusion can be interpreted as perhaps a mystic force of anti-colonialism and nature’s reclamation of the landscape. Lyndsey thus draws attention to the tragedy of the hanging rock as a mirror to the atrocities of colonialism. Another important allusion that Lindsey makes is the idea of the ‘lost child’ in Australian folklore and writing, that children stray into the bush to never be found. Stemming from the colonial cultural anxiety of isolation and the bush, this idea is thus continuously seen within Australian writing and repurposed by Lindsay to mirror the lived history of Indigenous communities and the stolen generation.

Late 20th Century Race Relations – Post-1967 Referendum

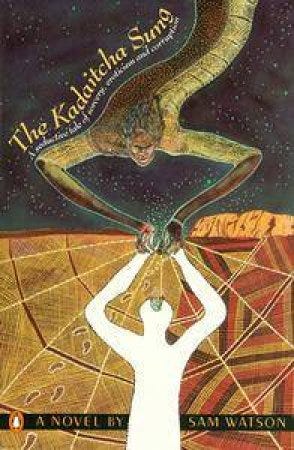

Post the 1967 Referendum on Aboriginal Rights the political context of Australia society was changing and evolving. The Kaidatcha Sung, written in 1990 by Aboriginal Australian activist Sam Watson is a novel of magical realism and a confronting text of vengeance and violence. The text begins with a central Australian myth that is then mirrored throughout the 20th century set text. The novel is a commentary on the removal of Aboriginal Australians from their homes, as an activist in Meanjin Brisbane, Sammy was a witness to the removal of Aboriginal people from their homes in Cribb Island and South Brisbane. An inherently political text, the novel takes place at the ‘end of the world’ where Australia is in a state of war. With an incredibly fluid narrative, a reflection of the idea of time immemorial in Aboriginal culture, the novel is a mix of Aboriginal mythology and an almost dystopian approach as a novel of magical realism. The setting itself, where Australia is a violent place of instability creates a dystopian feel to the text. Many critics of the novel have been disgusted by the language and violent events of the text, arguing that many of the acts of rape, alcohol and ultimately violence reinforce negative stereotypes. Nevertheless, Watson’s work as an activist and then experience of many Aboriginal people in the late 20th century is directly reflected by the novel. Watson would organise each event for Black deaths in custody to seek justice, especially in Brisbane, this is directly mirrored within the text where the main character is given the death penalty for killing a police officer he had never met – another political statement on the state of Australian race relations at the time.

Contemporary Resurgence:

The contemporary resurgence of these themes and the reclamation of Australian history by First Nations women is yet another testament to the power of literature to reflect societal change. The idea of ‘writing back’ against long held colonial ideas is a part of the movements of post and anti-colonialism. A novel that honours the sovereignty of Indigenous people, Carpentaria (2006) is a contemporary example of magical realism that similarly depict landscape and Australian society as monstrous but from a completely different perspective.

Alexis Wright’s Carpentaria is a massive epic set in north-west Queensland that fictionally addresses the very real issues of Aboriginal communities and land rights when it comes to minding companies. The text is at its core an allegory on the devastating impacts of colonialism. Similar to Sam Watson’s Capricornia, Wright blends the ideas of time and place to create a multi-layered text of memory, prediction and then immemorial nature of Aboriginal history. Once again, landscape plays a pivotal role within the text, as both the focus of the main conflict within the text and as intrinsic to Aboriginal Australian life. The connection to land and its existence and a presence is emphasised. When describing the land, Wright states “The old Gulf country men and women who took our besieged memories to the grave might just climb out of the mud and tell you the real story of what happened here.”[11] The statement ‘real story’ is an allusion to the traumatic legacy of massacres and stolen land that the text reflects upon.

Continuity and Change – From Then to Now:

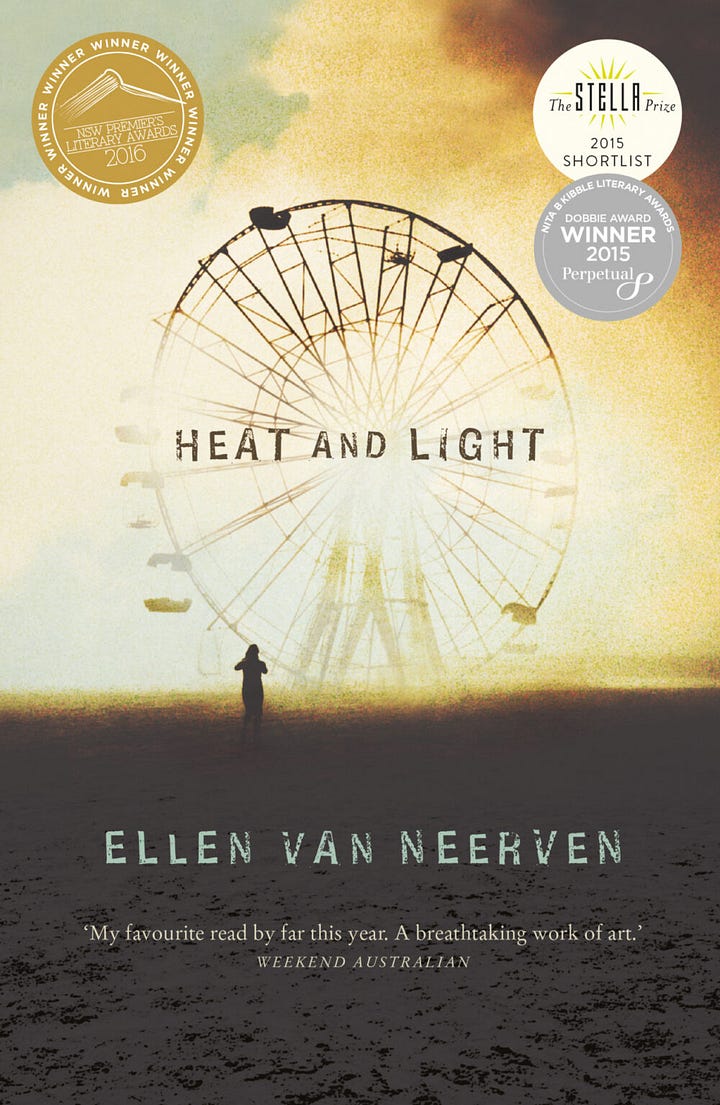

The first example of monstrosity, of isolation, and of Australian landscape, Le Relationi Universali as well as the early colonial text Never Never Land have incredibly similarities with the contemporary First Nation’s perspective contained within Elan Van Neervan’s 2014 collection Heat and Light. Each of these texts represents Australian landscape as something to be feared, nevertheless, the early examples fear the environment as a place of terror and untamed nature. In contrast, the terrifying landscape within Heat and Light is one of reclamation, of the land defending its rightful and sovereign owners against the affects of colonisation. Similar to the other novels from Indigenous writers, Heat and Light once again does not follow any typical structure, it does comprise sectioned stories, nevertheless, the true significance of these sections only comes to light after the conclusion of the book. The second section of the book, Water, is a long from dystopia set in the 2020s where Australia has become a republic. Within this text, Van Neerven imagines a race of ‘plant people’ who were created from experimentation on an Island.[12] Ultimately, these plants people are being ‘evacuated’ to create an ‘Australia2.’ As a mirror of Australian society, this evacuation and ultimately extermination of the ‘plant people’ directly mirrors the colonisation and massacre of Indigenous people but with a contemporary context.

The evolution of Australia and Australian national identity is thus consistently reflected within the key Australian literary themes of isolation, of landscape and environment and of fear and anxiety. From settler experiences of anxiety to contemporary texts representing the repressing affects of colonialism, Australia’s literary history is frankly dystopian in nature, without fully belonging to the genre. A combination of settlers writers, of female writers, of First Nations writers, Australian literary history is too diverse and too distinct to belong to genre, rather, it is a testament to the very diversity of Australian contemporary national identity.

Further Reading on the Topic:

Gibson, Ross. The Diminishing Paradise: Changing Literary Perceptions of Australia. Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1984. Herbert, Xavier, Capricornia, Sydney: Publicist Publishing Co. 1938.

Kennedy, Rosanne, and Sulamith Graefenstein. “From the Transnational to the Intimate: Multidirectional Memory, the Holocaust and Colonial Violence in Australia and Beyond.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 32, no. 4 (2019):403–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-019-09329-4.

Shoemaker, Adam. “Views of Australian History in Aboriginal Literature.” In Black Words White Page: New Edition, 127–58. ANU Press, 2004. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2jbkhp.11.

[1] “Le Relationi Universali,” 2020. https://collections.sea.museum/objects/12764/le-relationi-universali?ctx=503092895b4d8d1b1f246455cc2510b2a39e5bc6&idx=0.

[2] Gibson, Ross. The Diminishing Paradise : Changing Literary Perceptions of Australia.

Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1984.

[3] Shoemaker, Adam. “Views of Australian History in Aboriginal Literature.” In Black Words

White Page: New Edition, 127–58. ANU Press, 2004.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2jbkhp.11.

[4] Armstrong, R. E. M. The Kalkadoons: A study of an Aboriginal tribe on the Queensland

frontier. Brisbane: William Brooks & Co., 1980.

[5]“Centre for 21st Century Humanities,” n.d., https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres/detail.php?r=669.

[6] “Bulla, Queensland, 1861 [Picture] / W.O. Hodgkinson - Catalogue | National Library of Australia,” n.d., https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/catalog/4193269.

[7] Lucas, Thomas Pennington. The Curse and Its Cure. Brisbane: J.H. Reynolds, Printer, 1894. P.25.

[8] “Protesting 1938 & 1988 – From Capricornia to Oscar & Lucinda | Sydney Review of Books,” September 13, 2018, https://sydneyreviewofbooks.com/essays/protesting-1938-and-1988-from-capricornia-to-oscar-and-lucinda.

[9] Kennedy, Rosanne, and Sulamith Graefenstein. “From the Transnational to the Intimate:

Multidirectional Memory, the Holocaust and Colonial Violence in Australia and

Beyond.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 32, no. 4 (2019):

403–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-019-09329-4.

[10] Jane Lydon, “‘Little Gunshots, but With the Blaze of Lightning’: Xavier Herbert, Visuality and Human Rights,” Cultural Studies Review 23, no. 2 (November 27, 2017): 87–105, https://doi.org/10.5130/csr.v23i2.5820.

[11] Wright, Alexis. Carpentaria. Artarmon, N.S.W: Giramondo, 2006. P.11.

[12] Neerven, Ellen van. Heat and Light. St Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press,

2014.